William Pereira cut a charismatic figure nearly 60 years ago as he stood on a hilltop, overlooking a vast expanse of ranchland and citrus groves rolling toward the Pacific. He was imagining the shape of a city that might permanently change the face of American suburbs.

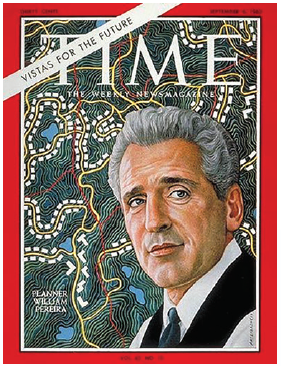

The Time magazine reporter accompanying the acclaimed architect described him in a long cover story as “a trim 6 feet with heavy-lidded blue eyes and an actor’s dash.” The wind swept through his wavy gray hair as Pereira related what he saw on that nearly blank canvas: a new, 1,000-acre University of California, ringed by 10,000 acres of master-planned villages whose residents could walk to schools, parks, entertainment and shopping. There was plenty of room for his vision, he said, adding: “This place is six times the size of Manhattan.”

As Irvine celebrates its 50th birthday, it’s a reason to remember Pereira, whose creativity helped guarantee the city’s quality of life. Just as he’d hoped, his design has given residents the freedom to leave cars in their garages and enjoy nearby parks and preserved open space.

The image of Pereira on that hilltop “says everything to me about my father – that he could see the future where there was almost nothing,” says his daughter, Monica, a Phoenix grade-school teacher. “He could see further than anyone I’ve ever known.”

In his more-than-half-a-century career, Pereira worked on more than 400 projects, including the CBS Television City studio, the University of Southern California, the Los Angeles County Art Museum and San Francisco’s striking Transamerica Pyramid. His global reach encompassed a naval base in Spain, an armed services headquarters in Indonesia, and a city and regional plan for Damascus, Syria.

By some accounts, Irvine was the closest to his heart. Pereira’s Master Plan conjured his hopes for a future in which people could live in harmony with their environment, absorbing population growth without compromising comfort. He called Irvine a “city of tomorrow.”

Pereira was born in Chicago in 1909. The son of a printer, he once said he couldn’t remember when he didn’t want to be an architect. Still, after moving to California in 1938, he enjoyed a stint as a Hollywood art director and producer, winning an Oscar for the set of “Reap the Wild Wind” by Cecil B. DeMille. He revered beauty in all things, according to his daughter, whose mother was the glamorous former model and actress Margaret McConnell. He drove a Bentley and wore impeccable black, three-piece suits.

Oscar winner, architect, planner

World War II helped return him to his passion for planning while inspiring what became his fierce environmental sensibility. As a civilian camouflage expert for the Army, he flew over the California coast, where, as he told Time: “I got a view then of the tragedies of helter-skelter planning, of the impossible traffic, the sprawling disorganization.” He was appalled by the pell-mell growth of suburbia, which offended him for its impact not only on humans but on the natural environment.

Pereira’s Master Plan conjured his hopes for a future in which people could live in harmony with their environment, absorbing population growth without compromising comfort. He called Irvine a “city of tomorrow.”

“He loved animals – dogs, cats and horses,” his daughter recalls. “He used to say: ‘Let’s give the animals bows and arrows and make this a fair fight.’ ”

Pereira voiced his despair in the Time profile, saying: “We have come to accept with enthusiasm the unprofessional, unappreciative, unskillful butchery of the land that goes under the name of planning.” In 1949, he became a professor of architecture at the University of Southern California, after which he worked on several high-profile projects, including the Los Angeles International Airport and the Bishop Ranch master plan, before he got his chance to offer a better idea.

A time of grand ambition

In 1959, the University of California regents hired Pereira to help identify the site for a future campus. He steered them to the 93,000-acre Irvine Ranch, later contracting with Irvine Company to master-plan not just the new campus, but a surrounding university city.

It was a time of grand ambition for planners all over the world. In the late 1950s, Oscar Niemeyer had helped create Brasilia, the new capital of Brazil, in that nation’s empty interior, while the Greek architect Constantinos Doxiadis designed Islamabad as the new capital of Pakistan. In the United States, real estate entrepreneur Robert Simon founded the model master-planned city of Reston, Virginia, in 1964. Like Pereira, Simon was inspired by the 19th-century “garden city” movement in Great Britain, which emphasized self-contained residential communities intermingled with green space and commerce.

The Irvine Ranch presented a unique opportunity. It was the world’s biggest private land-use project, having been preserved by the Irvine Company since the 1860s. Pereira envisioned the new campus as the center of a wheel, with spokes reaching into surrounding residential communities joined with nearby job hubs to afford easy commutes.

The basic idea had precedents. In the 1920s, the Janss Investment Co. sold land at a discounted price for a new site for UCLA while developing the Westwood neighborhood around it. In 1951, Stanford provost Frederick Terman conceived the Stanford Industrial Park, a university-affiliated business center that generated income for the university and city. Yet before Pereira, no one had built a university city from an architect’s drawing board.

Pereira’s original plan would have preserved 20,000 acres of farmland and 30,000 acres of mountain wilderness for recreation. While much of the farmland was developed as the plan evolved, nearly twice as much open space as Pereira imagined has been permanently protected.

Pereira’s bold choices were sometimes ahead of his time. The Transamerica Pyramid – today an internationally praised urban icon – sparked controversy before and after its 1972 completion. Since then, it has become a San Francisco icon.

Pereira died of heart failure in 1985, at age 76. His obituary in the Los Angeles Times said: “Bringing thought and style to Los Angeles’ helter-skelter growth was what Pereira was all about. His stylish yet efficient architecture dominated the look of Los Angeles for more than 30 years.”

“I’ve often thought about how he would react to Irvine now,” his daughter says. “All the roads he planned are still there. The only thing he maybe wouldn’t have been able to envision is how the trees have grown.”

She added: “I would give almost anything to go back and ask him: ‘How were you able to do that? Why were you given a gift no one seemed to have?’ It’s amazing to think how many people trusted his vision without ever being able to see it for themselves.”